The Learning Cycle: Experience

- Kat Peters

- Apr 26, 2021

- 6 min read

The best learning happens when we consider our own lived experiences, ask critical questions about them, and make a change. This week: Experience.

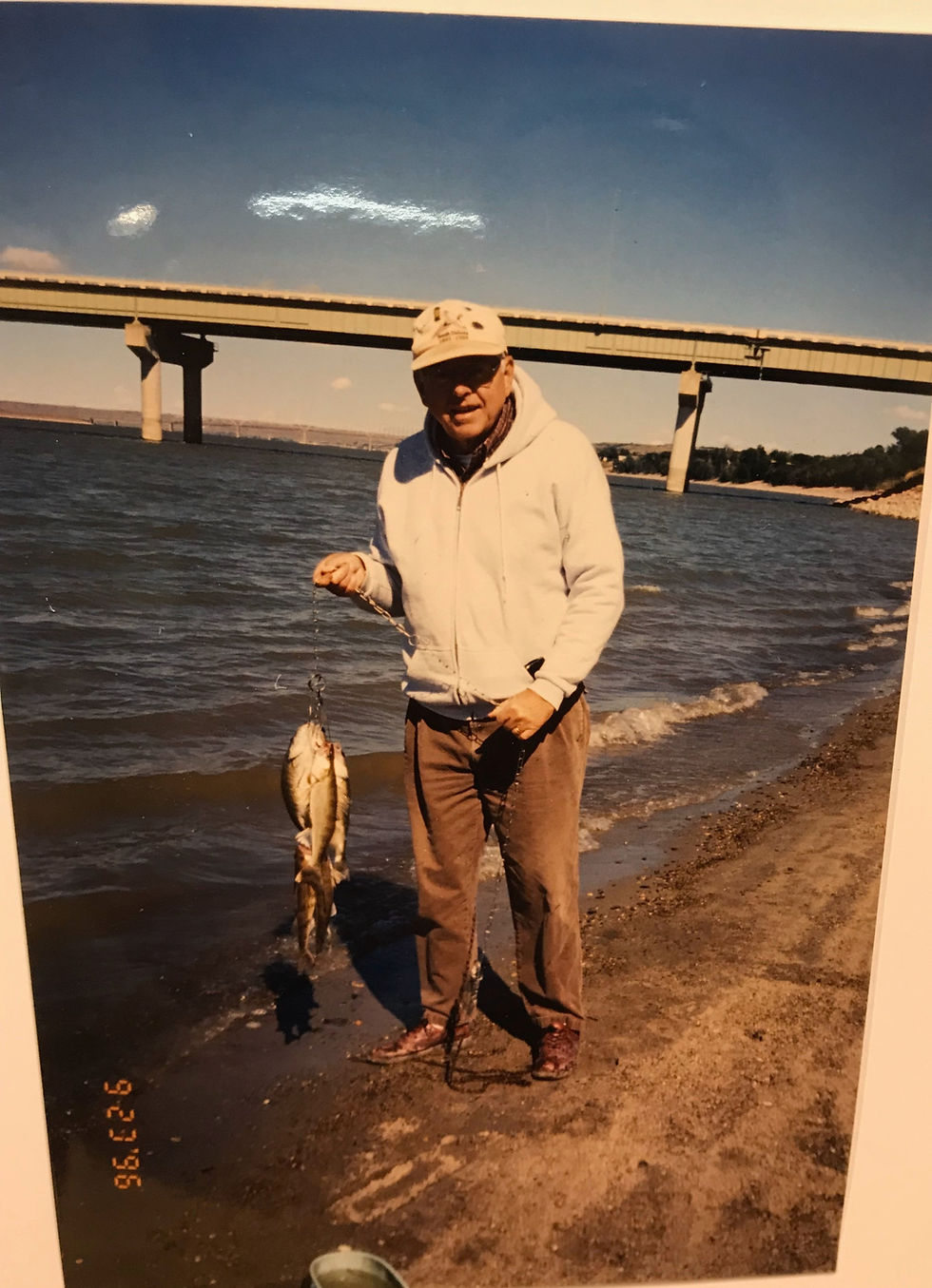

My grandpa was one of the most loving people in my life, and I'm lucky to have had him around until just last year.

In my life and in my work in study abroad and cross-cultural education, I have come to appreciate the work of Paolo Freire and other popular educators from Latin America and around the world. They show us that learning does not just happen from reading books, but from analyzing our own lives, asking hard questions about what we experience, and working with others to take action to build a better world. These actions are then also fodder for further reflection. The whole process is called concientizao (in Portuguese), or concientización (in Spanish), or consciousness/awareness-raising in English, though it goes far beyond awareness and into action.

This is an idea put forward by several educators in the 1960’s in Latin America, especially Brazil. Educators and activists there were realizing the importance of literacy for the masses, especially as a tool with which to confront oppression. These educators began to think about how they could teach literacy, and they realized that books like Paco and Lola (the Dick and Jane of the Spanish-speaking world) had nothing to do with the lives of the poor.

In my course on literacy in my Master’s in Education, we learned about this concept. Modern-day, middle-class United States teachers are encouraged to have students write their own stories to practice reading, as the students will be much more interested in reading something that they themselves or their classmates have written. But popular education goes beyond literacy to get at making life better for the most vulnerable.

The popular educators in Brazil realized that if people were not learning from their own lives, not only would they have trouble learning to read, but their newfound literacy would not lead to a better life without an explicit link to their lived experience. So, that’s how Freire and others began to teach reading from the lived experiences of the people. They began by talking about what was going on around them, and then they learned to read and write the words of their lives: well (pozo), for example, as in “the well is going dry.” The educator/facilitator would write the word “pozo” on the board, and talk about the letters in this word, and everyone would practice reading it and creating other words that used the same letters.

Thus the learning had to do with the experience of the people themselves, not just about the official story as expressed by some authors or the media or politicians. The groups of learners were learning together, in a group where everyone’s experience mattered.

This was done in a context where the facilitator planned and led lessons and provided information that would be of benefit to the students, with one of the goals being an ability to problematize the experiences that were being shared. Problematizing means analyzing the experience in light of important information, understanding the experience from a perspective that considers the emotions, but that is not driven by emotions.

For example, the Brazilian peasants began to ask themselves: “Why don’t we have water?” And as they continued to learn to read, they were exposed to information that told them that their aquifer was being used by nearby large-scale agricultural endeavors. The experience then provoked reflection, otherwise known as problematizing.

But the new understanding does not end there; it leads to action, or a change in behavior. In the example above, the peasants were empowered to protest the loss of their water, to speak up to their government, to seek out ways of addressing the issue that was affecting them.

You can see that this process places importance not just on what one is learning, which is of vital importance, but also on how one learns. The theory (telos) is important and must be present, but the experience (praxis) must influence theory, and also be influenced by it, with a constant attitude of reflection and learning. So, concientización is an on-going process, best accomplished in a group setting, and it has a goal the creation of new knowledge and new ways of being in the world.

In my work and writing I would like to use some of these same ideas to help guide us in our experience and reflection. The activities you have in your life are important as experiences that are rich in reflective value and can contribute to learning. Here is a short bit of story from my grandfather, Charles Jarratt, about his experience as the owner of a grocery store in small town (Canistota) South Dakota. You can read more about some of my experiences throughout the blog. What about you? What are some of your most important life experiences?

Next week we’ll talk about asking questions.

My grandpa, Charles Jarratt, and his parents, George and Katherine.

From "The Store," written by Charles E. Jarratt:

““The Store” was originally called the Farmers Union Supply Company, later known as the Farmers Store. To our family it was just “The Store.” It was incorporated in January 1920 by area farmers who wanted to own a general merchandise business. They hired George Jarratt [Kat’s great-grandfather, Charles’s father] as manager. George was a farmer who first walked to town to his job. He later rented a room from Mr. and Mrs. Henry Haas. After he had managed the business for some years he decided to buy the shares of the farm owners. He did this in the 1930s when the business was struggling. The stockholders understood that he had no money to buy their stock so they generously sold to him by taking groceries and other merchandise for shares.

“The building, a frame structure located on a corner of the main street of Canistota, was directly east of the Ortman Hotel. The building was 142 feet long and had a full basement under the north half and a second story at the rear of the building that was used at one time for an office and storage.

“The basement was used for storage of the coal burning furnace that was the main heating plant at one time. There were shelves for canned goods that would not fit in the shelves in the upstairs main selling area. There was also another room where things were stored when the weather was too cold for storage in the upstairs backroom. Eggs were candled also in the basement.

“The ground level floor was divided into several rooms including the main selling area which was about one-third of the space. Through a door at the rear of this area was another storage room. Next were the stairs to the office on the second story. The next room had a large door to the street for unloading truck loads of groceries and there was an enclosed wire screened room used for storage of flour. This was called the “flour house.” Near the flour house was kept the glassware that was given as a premium when purchasing flour. (This glassware, now known as depression glass, is in demand for antique buyers.) The next room was for the storage of salt blocks, kerosene tank and even Christmas trees during the winter season. A small building called the chicken house was attached to the end of the main building. You guessed it. They even bought chickens from the farmers.

“George was a very conscientious business man. Service to the customer was very important. It was a custom in those days for the farmer to bring the “grocery list” to the store so the grocer could “fill” it while the farmer did some other business in town. If it so happened that the store did not have a certain item on the list then one of the clerks would go to a competing store and buy the article to complete the order. Hence the customer never knew that the store was out of a certain thing. But the real reason was you did not want your valued customer to go to the competition. Customers were very loyal to a business so the owner was willing to go to great lengths to keep them. It was quite often my duty to go to the other stores to pick up the needed item. It was rather embarrassing to do this, but you did it to keep your customers…”

… My grandpa’s writing continues to explain more about the store. He also wrote down many stories about living in a small town, hunting for ducks and geese over his lunch break, going fishing on the Missouri River, and other stories.

With his catch at the Missouri River in Chamberlain, SD. I snapped photos of these and other photos that were on display at my grandpa's funeral last March, just days before the Covid-19 lockdown began.

Comments